"We can manage our own destiny" (Credit: Nori Jemil)

The people of the Faroe Islands have been raised in the belief that we can manage our own destiny,” said Magni Arge, Faroe Islands MP in the Danish Parliament.

A long struggle for independence (Credit: Nori Jemil)

A long struggle for independence

The Faroes are an archipelago of 18 verdant, volcanic islands jutting out of the Atlantic Ocean between Scotland, Iceland and Norway. With a Celtic and Viking heritage – and a population of about 50,000 – they’re semi-autonomous but still a Danish dependency, having been ruled by both Denmark and Norway for centuries.

The Faroese have had a long struggle for self-rule, which had a turning point during World War II. Denmark was occupied by the Nazis, and it was Britain that provided protection from German invasion due to the islands’ proximity to the Shetland Islands and UK mainland. With no contact with Denmark for five years during the war, the islanders began to forge their own path.

Over the last few decades, many Faroese have been building towards a new wave of independence, including the struggle to not only hold on to their native tongue, but also to help it flourish.

The fight to keep a language alive (Credit: Nori Jemil)

The fight to keep a language alive

The Faroese people have been fighting to keep their language alive ever since it was suppressed by the Danish, when the islands became part of the Dano-Norwegian Kingdom in 1380. With the Reformation, that stronghold was reinforced and Faroese was completely banned in schools. People had no choice but to succumb to the vernacular of the law courts and the Danish parliament.

While Danish dominated official realms for centuries, the wider community continued to speak and sing in Faroese. The written language they use now only formally came into being in 1846, and over the next few decades an upturn in the Faroese economy, caused by sloop fishing and the end of the Danish trade monopoly, further increased national confidence.

With greater links to the outside world in the late 1800s, people began to assert the integrity of their own tongue, and oral Faroese became a school subject in 1912, followed by the written language in 1920. After the establishment of Home Rule in 1948, Faroese was recognised as the official language of government; however, Danish is still taught as a compulsory subject, and all the Faroes’ parliamentary laws still need to be translated into Danish.

A culture shaped by a remote world (Credit: Nori Jemil)

A culture shaped by a remote world

Faroese culture, identity and language have been shaped in part by the windswept islands’ harsh climate and far-flung location. The need to work together to survive has given these islanders a strong sense of community and a dogged refusal to let go of a way of life that has sustained them through unforgiving winters, war and disease.

Farmer and landowner Jóannes Patursson is the 17th generation of his family to live in the village of Kirkjubøur. Part of his home doubles as a museum, which is testimony to the ancient ways of life still practised here, such as fishing and animal husbandry. His great-great-grandfather was the poet and nationalist of the same name, and like his forbears, Patursson continues to strive for a society that puts locals in charge of their own future.

Language is as important to him as it was to his poet ancestor, and he can tell you the traditional name of every fishing and hunting tool on display in the museum. His house backs onto St Olav’s church, and he serves as a warden here for the monthly Sunday service, ringing the bell and greeting parishioners in his national dress.

A community brought together (Credit: Nori Jemil)

A community brought together

Kirkjubøur is one of the Faroe Islands’ most important settlements. Not far from the capital Tórshavn, it is the most southerly village on the largest Faroe island, Streymoy. During medieval times, it was the centre of religious and cultural life.

Two pieces of architecture, which dominate the clutch of small wooden houses dotting the landscape, testify to this past. The imposing ruins of the 14th-Century Magnus Cathedral sit alongside the smaller, white-walled St Olav’s church (pictured), or Ólavskirkja, which dates back to the early 12th Century and still serves the local community.

Inside, most people can point to where they used to sit with their parents as children, and outside to the plots where their parents have now been laid to rest. Many also remember when they had to battle to have any religious services in their own language – it was only in 1961 that the first Bible was published in Faroese.

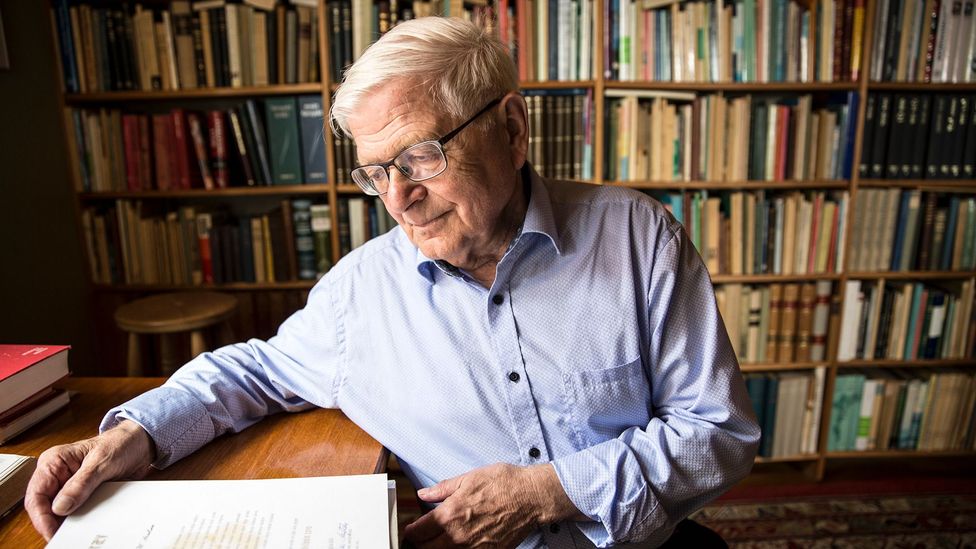

The man known as 'Dictionary’ (Credit: Nori Jemil)

The man known as 'Dictionary’

Academic Jóhan Hendrik Winther Poulsen’s identity is firmly rooted in Kirkjubøur soil. From St Olav’s he can see across the water to Skopun, the small village he grew up in. And it was to Kirkjubøur that he gravitated, marrying his sweetheart Birna, and becoming a stalwart of the community and raising four children.

He may have started life in a small village, but Poulsen’s name will be writ large in the annals of Faroese history. Now retired from his life of academia, he is best known as the man who produced the first-ever Faroese-to-Faroese dictionary, gaining him the nickname Orðabókin (Dictionary), and his children the monikers sonur Orðabókina (son of Dictionary) or dóttir Orðabókina (daughter of Dictionary).

In the late 1960s, academic and poet Christian Matras asked Poulsen to return from the US, where he was teaching Scandinavian languages. Matras had written a Faroese-to-Danish dictionary in 1961, and wanted Poulsen to create one that only used Faroese meanings for Faroese words. Such a dictionary was the vital next step for the Faroese to retain their own tongue. And so, for 30 years, until the dictionary’s publication in 1998, Poulsen worked with a team of linguists at the University of Tórshavn to complete it.

Academic Jóhan Hendrik Winther Poulsen created a dictionary (Credit: Nori Jemil)

You see, we Faroese are a bit puristic, so we like to have our own words,” Poulsen said.

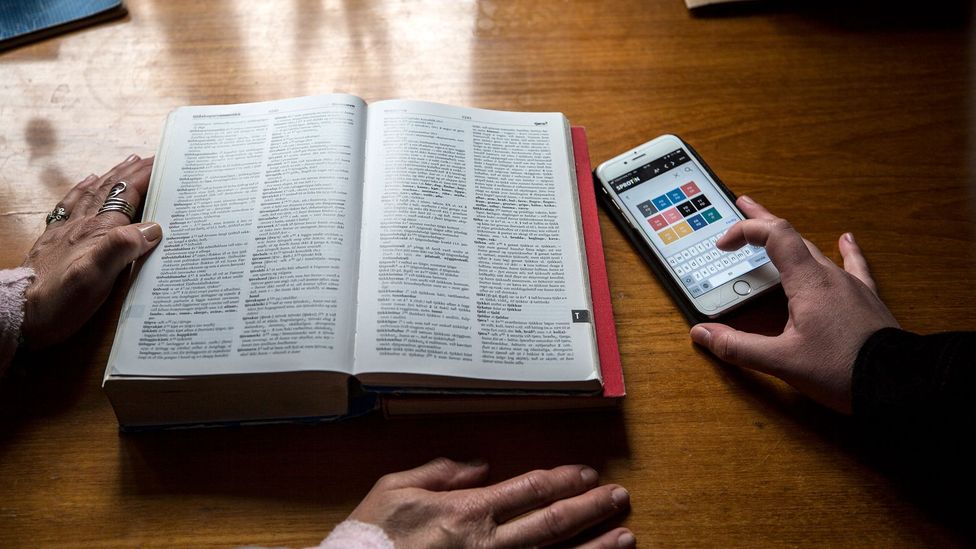

Old words for new things (Credit: Nori Jemil)

Old words for new things

But to compile the dictionary, Poulsen needed new Faroese words to describe things – such as modern technology – that were not in existence when Danish became the islands’ official language.

He came up with new words by using connections to an older, pastoral way of life – like skiggi for computer screen, for example, an old Faroese word that describes the sheep’s gut once used to keep rain out of chimney holes; and flöga for CD, which derives from the practice of flattening harvested hay bales.

During his work on the dictionary, Poulsen presented a radio show that discussed issues surrounding the Faroese language. When he asked listeners to send in any Faroese words that had fallen out of common usage, he was astounded at the enthusiastic response. To this day, people stop him in the street with a new word, and he’s sometimes credited with words that came into existence long after his retirement – like geymi for a USB drive.

A life of song and dance (Credit: Nori Jemil)

A life of song and dance

Before there was a dictionary, however, the Faroese had other ways to keep their language and culture alive. While their own tongue wasn't spoken in court, churches or schools, the islanders continued to converse amongst themselves in Faroese. Like the Icelanders, they have a strong oral tradition, and a legacy of ballads and epic tales that are a source of national pride.

Originally coming from France and other parts of Europe in the 13th Century, the ring or chain dances survive to this day. They enabled islanders to get together, link hands as a community and tell tales of their beginnings – and of a life before language was written down, of harsh weather and gathering inside in the warmth with a fire and food.

And while some of the ballads, or kvæði, are in Danish as well as Faroese, the islanders have imbued them with so much of their own dialect and intonation that a Dane would be hard-pressed to recognise some of their own words.

The lifeblood of a village (Credit: Nori Jemil)

The lifeblood of a village

A short ferry ride from Tórshavn on Streymoy is the smaller, greener landmass of Sandoy. On the island’s south-eastern side is Dalur, a community at the heart of the kvæði. Here, ballads are seen as the lifeblood of the village, having been sung and danced here for hundreds of years.

The community hall even has a sprung floor for dancing, so that when gatherings culminate in a chain dance they can literally feel the power of the group moving together as the floor resonates with each rhythmic step.

Fashionable people (Credit: Nori Jemil)

Fashionable people

On special occasions, like formal chain dances, national dress is always favoured. The clothing is a strong part of Faroese culture, and many people wear theirs for family photos, special church services and at the end of July for National Day.

Despite the islands being made up of a number of remote settlements, the people here are surprisingly outward-looking and quite stylishly elegant, combining winter knits with traditionally embroidered waistcoats and jackets for an eclectic and colourful look. (Knitwear designers Gudrun & Gudrun, who created the pullover for The Killing’s character Sarah Lund, are based in Tórshavn.)

A land that sustains (Credit: Nori Jemil)

A land that sustains

Given the difficult climate, keeping themselves alive, let alone their traditions and language, might have seemed impossible. But the Faroese people have found ways to prosper here, using the thin layer of top soil to grow their prized potatoes, angelica and rhubarb, and making good use of the abundant seas and wildlife.

Over the centuries, inhabitants have learned to live sustainably, taking only what they need from nature’s cupboard. Food is cooked fresh, and very little, if anything, is thrown away. Sheep roam freely over the green hills and graze on every blade of grass, and they’re sometimes lowered down to cliffside pastures via a rope to ensure that every patch of land is used effectively.

A nod to the sea (Credit: Nori Jemil)

A nod to the sea

Just like their ancestors, who dried, fermented and preserved food, most islanders still have a drying shed in which to store things for leaner periods. Even those in modern housing in Tórshavn usually have a larder in which they'll keep a shoulder of lamb, preserved in brine in a heavy ceramic pot.

The Faroe Islands have become known for their culinary expertise too. It may seem rustic from the outside, with its turf roofs and typical wooden structure, but the restaurant Koks (pictured) serves up Instagram-ready, Michelin-starred dishes using traditional ingredients like crustaceans, dried fish and rhubarb. There are also a number of restaurants by the water’s edge, like Barbara Fish House and the newly opened Skeiva Pakkhús that specialise in fish and seafood in a more family-orientated environment.

An independent way to fish (Credit: Nori Jemil)

An independent way to fish

The Faroese are renowned for their courage at sea, and account for a significant number of officers in the Danish Navy, according to Magni Arge, Faroe Islands MP in the Danish Parliament. Many locals make their living from fishing in the treacherous North Atlantic waters; in fact, the Faroese economy is dependent on fishing and fisheries, with the surrounding ocean offering excellent conditions for salmon farming as well as a new seaweed industry.

Locals are proud of being able to determine their own quotas – one of the reasons they have never been part of the EU, despite Denmark signing up in the 1970s.

A new constitution on the horizon? (Credit: Nori Jemil)

A new constitution on the horizon?

The Faroese have a long history of discussion, democracy and government, and Tinganes (pictured) in the capital Tórshavn is claimed by the Faroese to be one of the oldest parliamentary meeting places in the world. The current building inhabits the site of the first Viking parliament that met here sometime after 900AD.

The current drive to write their own constitution is the next stage in the movement towards what many Faroese hope will be self-governance, though it’s a controversial issue for some, given how much financial support is received from Denmark.

Nevertheless, the Faroese are keeping a close eye on how Catalonia’s bid for independence progresses, as well as Britain after Brexit. Separatists feel that independence is long overdue, though for many, the spike in taxes if they were to lose Danish support is more than enough reason to keep some of the ties that bind them. Whatever does happen in the future though, the fight to keep Faroese as a living, breathing language will endure.

“Everything had its name tied into the old Faroese language" (Credit: Nori Jemil)

Everything had its name tied into the old Faroese language, and if they lost that they would probably lose the ability to live here also,” Patursson said.